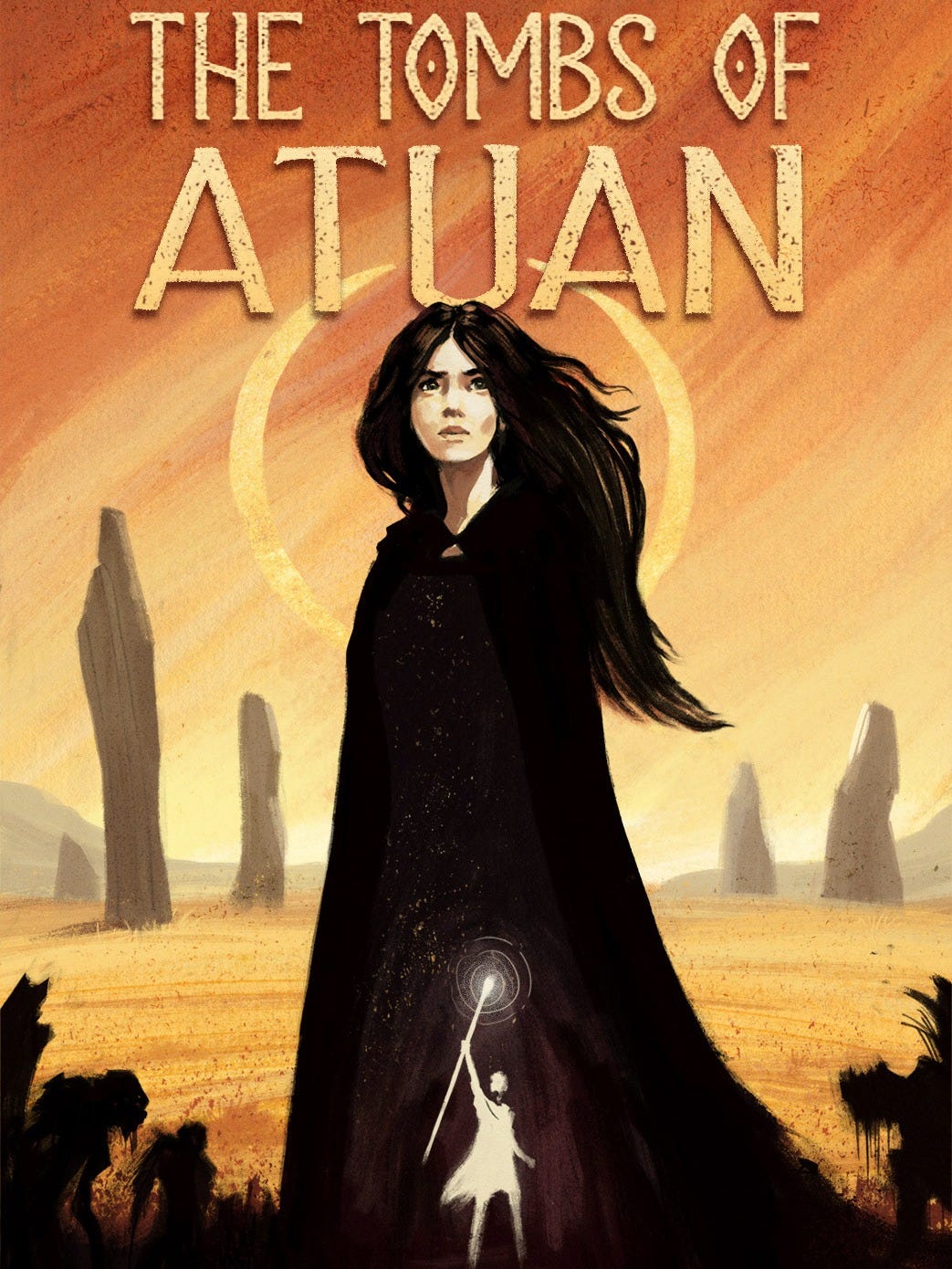

Identity and the coming of age are major themes of the Earthsea series by Ursula K. Le Guin. The first book, A Wizard of Earthsea, tells of Ged – a rash young wizard who must struggle with his inner demon in order to reach his true potential. While I enjoyed this book, and found it a compelling coming-of-age story, it does not compare to the second book in the series, The Tombs of Atuan.

This book is not about Ged – in fact, he does not appear until midway through. Its protagonist is Tenar, a girl from the land of Kargad, who, at a young age, is taken to be the High Priestess of the Nameless Ones. She is forced to give up her home, her family, her freedom, and even her name in their service, becoming known as Arha – the Eaten One. Growing up, she meets an older, wiser Ged, who is on a quest to unify the lands of Earthsea and asks her to join him.

The Tombs of Atuan is not The Lord of the Rings or The Wheel of Time – it is not a massive, grand fantasy adventure, a quest to defeat a dark lord with the fate of the world hanging in the balance. It is something far more intimate and personal – the story of a single girl and her personal growth.

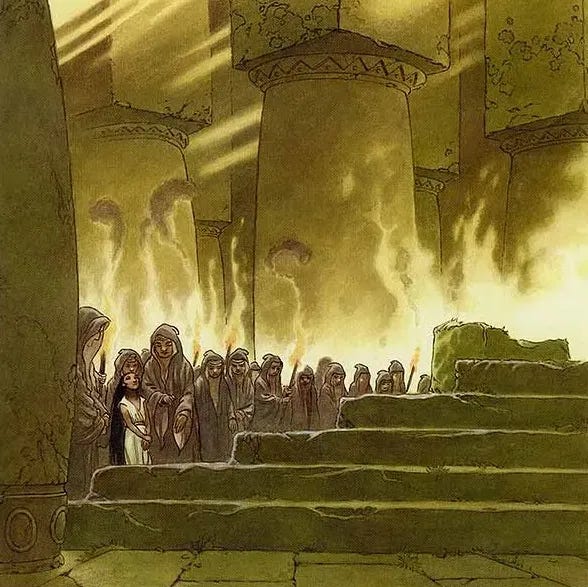

Religion and Control

A major theme of this book is control. As High Priestess, Tenar might nominally have power over others – but the story shows us jut how purely nominal this power is. She cannot leave the temple complex, which itself is in the middle of the desert, far away from the true centers of power in Kargad. She can do nothing besides perform the rituals entrusted to her. She is not even viewed as a person – rather, she is seen as a reincarnation of every High Priestess before her. Every piece of her individuality, of who she is as Tenar, is systematically chipped away. She is only Arha, High Priestess of the Nameless Ones.

Religion can be a beacon of hope for people. It can provide peace of mind, and promote the development of moral values. It can also be used to chain people, to keep them confined in belief systems that only hurt them. Tenar doesn’t even realize how trapped she is. She doesn’t wish for anything else – she has been taught since childhood that there is nothing else.

We see this in her interactions with others – she is shocked to see that no one else cares about the gods the way she does – they care about themselves, or about gaining power. This can be seen as a reflection of the real world, where a depressingly number of people see religion only as a means to an end - that end being power.

The book vividly describes the destruction of faith. Ged makes Tenar realize that the Nameless Ones are evil creatures that do not deserve her worship. He convinces her to give up the name of Arha and reclaim her identity as Tenar. Even when their escape is successful, she struggles mentally. Her entire belief system was destroyed. Everything she had ever believed in was turned on its head. Her only home was gone, as was the identity that she had held onto for most of her life. Her emotional struggle, and search for meaning is captured perfectly.

A dark hand had let go its lifelong hold upon her heart. But she did not feel joy, as she had in the mountains. She put her head down in her arms and cried, and her cheeks were salt and wet. She cried for the waste of her years in bondage to a useless evil. She wept in pain, because she was free.

What she had begun to learn was the weight of liberty. Freedom is a heavy load, a great and strange burden for the spirit to undertake. It is not easy. It is not a gift given, but a choice made, and the choice may be a hard one. The road goes upward towards the light; but the laden traveler may never reach the end of it.

Breaking Free

The catalyst that changes Tenar’s life is the arrival of Ged, whom she traps in the labyrinth. Driven by curiosity, she does not kill him, but rather talks to him. With any other author, this would have turned into a romance. It’s not an uncommon story – an inexperienced girl is seduced by a mysterious stranger who takes her with him to experience the world. But Le Guin doesn’t go down this path. This story is not about Ged, but Tenar; he is present only to highlight her innate goodness and provide a catalyst for her to leave. She leaves the temple not because she loves him, but because he shows her just how wrong and harmful the system she serves truly is.

Le Guin makes masterful use of the element of darkness in this novel – as part of her duties, Tenar wanders the underground labyrinth and cave system that holds the treasures of the Nameless Ones. A place where no light is allowed, only a series of extremely specific instructions keeps her from getting lost and dying in the dark. Skillful prose perfectly captures that feeling of fear, of blind helplessness. And yet, when Ged uses his magic to illuminate the cave system, its true appearance is revealed – the caves are carved of beautiful crystal, and Le Guin eloquently describes their stunning beauty.

The darkness of the caves is a symbol of ignorance and fear. Ged’s light symbolizes courage and wisdom. Tenar learns not to feat the light; she learns that, though she was in the clutches of the dark, she is the light.

Conclusion

Ged promises Tenar that they will return to his land as heroes, that she will be a princess among his people. But she realizes what he does not – that that would be just another form of captivity. She wishes, in the end of the book, not for fame, but for a simple life – a life where she can discover who she truly is, and then learn to be herself without the expectations of others.

While The Tombs of Atuan was written for children, I believe it can be enjoyed by all ages for its simple message. It is, at its core, story about identity – no matter how people try to crush it, it is not something that can ever be lost.